Holes. “Holes” is kind of like movie appreciation 101 for the youth market. It is a story of adolescence, about a boy who comes from a family of mishaps. He is mistakenly convicted of stealing a pair of shoes from a famous athlete. He is sent to a juvenile detention camp in the middle of the desert, where unbeknownst to the authorities, the warden has all of the detainees digging holes in search of a buried treasure.

Holes. “Holes” is kind of like movie appreciation 101 for the youth market. It is a story of adolescence, about a boy who comes from a family of mishaps. He is mistakenly convicted of stealing a pair of shoes from a famous athlete. He is sent to a juvenile detention camp in the middle of the desert, where unbeknownst to the authorities, the warden has all of the detainees digging holes in search of a buried treasure.It is an almost typical setup for a young adult film, where kids are misunderstood and are pushed around by authority figures that either don’t deserve or have come to abuse their power. But the complexity of the story and its structure suggests a much more intelligent and engaging vehicle than can typically be found in the matinee features of the multiplex. The storylines of the characters are all interconnected in ways that are revealed slowly throughout the entire length of the picture, much like a Robert Altman film or even a good noir. It is necessary to follow many small details from the beginning of the story through to various points throughout, engaging the mind in a much more participatory way than a typical young adult film.

“Holes” also marked the official cinematic introduction to the rising star Shia LaBeouf, who recently has ruled the box office for multiple weekends in the thriller “Disturbia” and promises to trump that feat this summer as the primary flesh and blood star of the CGI robo-sci-fi mega-blockbuster “Transformers”. Although Labeouf is supported in “Holes” by some major adult talent, including Sigourney Weaver, Jon Voight, Henry Winkler and Tim Blake Nelson, and is directed by action guru Andrew Davis of “The Fugitive” fame; it is obvious that LaBeouf is a star to be.

Labeouf carries the entire movie, from far flung detail to the more obvious clichés of the genre. I imagine the only reason his star took so long to rise from his introduction here in 2003, is that he took his time to finish school before grabbing hold of that inevitable Hollywood career.

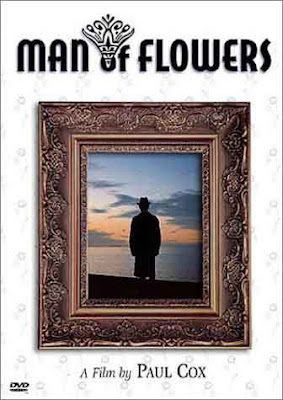

Stroszek and Man of Flowers. With this year’s Overlooked entries by German visionary Werner Herzog and Australian auteur Paul Cox, we venture into the realm of films that are often referred to by less versed cineastes as “difficult films.” This is a label that is not entirely an unwarranted disclaimer. Even when I’m enjoying a film by say… David Lynch, I find myself wondering just how he can expect any normal filmgoer to enjoy, let alone understand his work. But enjoyment is not exclusive to understanding and these are films that are not intended for the average movie audience.

While these two films do share some of the difficult traits of the majority of Lynch’s work, they each wind up with a clear understanding of the events they portray by their divine conclusions. But by that point in each film I had already achieved a great appreciation for what these films were exploring and the understanding became merely a bonus feature. There is such beauty in the way Herzog’s and Cox’s characters experience their lives and their surroundings that meaning becomes secondary.

In Cox’s “Man of Flowers” we are introduced to a gentleman, Charles, who is obsessed with flowers to the point where flowers and music are the only things that can arouse him. He pays an artist’s model to strip for him, but he never touches or speaks to her and even finds himself unable to watch her before she’s finished. When he is uncomfortable he goes to the church next door and plays horrific, yet beautiful melodies on the pipe organ.

In Cox’s “Man of Flowers” we are introduced to a gentleman, Charles, who is obsessed with flowers to the point where flowers and music are the only things that can arouse him. He pays an artist’s model to strip for him, but he never touches or speaks to her and even finds himself unable to watch her before she’s finished. When he is uncomfortable he goes to the church next door and plays horrific, yet beautiful melodies on the pipe organ.The model, Lisa, is trapped in a relationship with a financially dependant artist, David, who was once considered great and now suffers through a drug habit. She likes Charles and eventually leaves the artist to pursue a relationship with a girlfriend, all the while remaining close to her flower man. David sees Charles as his opponent for Lisa’s love and when his drug money runs dry decides to fleece the money from the well-to-do Charles. Charles’s solution to the problem of David is inevitable, yet poetic and enlightening after the fact.

Of course this synopsis has just the opposite effect that the film itself has in the way its logic is impenetrable and dismantling until the resolution of the story. And instead of focusing on the “plot”, there is a beauty in watching how these people so desperately search for the meaning of their actions just as the audience does.

In Herzog’s “Stroszek” the meaning is not as elusive, but is still not the entire point of the exercise. Bruno Stroszek is released from a Berlin prison in the opening moments of the film, with no place left to go but his former life. Despite his problems with alcohol, which landed him in jail in the first place, Stroszek seems to be a thoughtful and sensitive man. He befriends a hooker, Eva, whose pimp is abusive to both her and Stroszek.

In Herzog’s “Stroszek” the meaning is not as elusive, but is still not the entire point of the exercise. Bruno Stroszek is released from a Berlin prison in the opening moments of the film, with no place left to go but his former life. Despite his problems with alcohol, which landed him in jail in the first place, Stroszek seems to be a thoughtful and sensitive man. He befriends a hooker, Eva, whose pimp is abusive to both her and Stroszek.Eventually, Stroszek decides to make a new life in America, bringing Eva and his neighbor, who has relatives in Wisconsin, with him. The neighbor’s relatives set Stroszek up with a job and a plot of land in Wisconsin where he can put a mobile home and begin his new life. The “Land of Opportunity” does not prove as bountiful as its reputation however, and soon Stroszek sees his woman leave him for a life of selling her body once again, his mobile home auctioned off by the bank to the highest bidder, he cannot communicate with anyone since he hasn’t learned the language, and he can’t even seem to land himself into the familiar environment of prison.

Once again this synopsis makes the film sound a little more clear-cut than it actually is. But instead of Cox’s in depth dissection of his character’s motivations, Herzog is interested in painting a portrait of these character’s experiences through images. There is Stroszek in Berlin playing his accordion shows in the tenement court yard, the desolate Wisconsin landscape upon which the mobile home is placed and later removed, the rows and rows of semi-tractor trucks parked outside the truck stop where Eva waits tables, and the Native American themed amusement park with its totem pole chair lift.

Herzog prides himself as being able to capture the unique visuals that reflect life on our planet, and his gift is on full display here. His best image, providing the closing commentary on the entire film, is a dancing chicken that is compelled to keep starting the music to which it has been trained to respond. A policeman adds to his call for backup, “…and we can’t stop the dancing chicken.”

Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus. What a compelling and strange documentary is Andrew Douglas’s “Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus”. It is a dissection of the highly religious backwater communities of the ultra-rural south seen through the eyes of bluegrass musician Jim White, based on his 1997 album “The Mysterious Tale of How I Shouted Wrong-Eyed Jesus”.

Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus. What a compelling and strange documentary is Andrew Douglas’s “Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus”. It is a dissection of the highly religious backwater communities of the ultra-rural south seen through the eyes of bluegrass musician Jim White, based on his 1997 album “The Mysterious Tale of How I Shouted Wrong-Eyed Jesus”.White guides the film from the point of view of both outsider and one of the initiated. Having been born in California before moving to the Deep South, White was always an outsider in his community as a child and young adult; but with age and wisdom came an appreciation for what oddball perspectives these backwater communities offered their residents. White expresses a deep love for the people and lives of this depressed country.

That sense of depression is carried through the soundtrack of southern blues songs provided by White and other musical guests, including Johnny Dowd, Lee Sexton, and The Handsome Family. The film goes beyond documentary in it presentation of the music, which entails staged performances on location. There is one performance by The Handsome Family that takes place on a house floating down a river, blending the music intrinsically to the environment which surrounds it and it enhances.

“Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus” is like no other documentary I have ever seen. It is a document in mood and environment, rather than fact. Rarely does a film so wholly capture the true essence of the environment on which it is commenting.

I can’t help myself but provide two clips from this day’s wonderful line-up of films. The first is the Handsome Family performance mentioned above, the second is Herzog’s dancing chicken.

No comments:

Post a Comment